The Toronto Star, Sept 5, 2013

The legendarily creepy Canadian director gets his due as six artists kick off an autumn-long homage to his 40-year career.

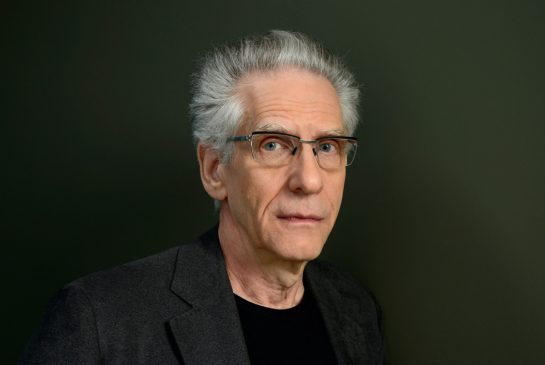

Director David Cronenberg was on hand Thursday to help introduce the massive homage in his honour. LARRY BUSACCA / GETTY IMAGES

By: Murray Whyte, Visual arts, Published on Thu Sep 05 2013

Fall 2013 is David Cronenberg season in Toronto and, depending on who you talk to, it’s about time. The legendary — and legendarily creepy — Canadian director just finished his 21st feature film, Maps to the Stars, shot here at home in Toronto, and almost as legendary as his unique brand of auteurship is his loyalty to the city that spawned him (if you’ll forgive the term).

Officially, the autumn-long homage to the director is called The David Cronenberg Project, and it’s being stewarded largely by the Toronto International Film Festival. You could almost see the pair as Siamese twins, a conjoinment metaphor Cronenberg would no doubt enjoy in its weirdness. It’s nonetheless apt, as the pair have grown bigger, better and stronger together through the 1980s and ‘90s, arriving fully formed in the 21st century at the upper strata of the global film industry.

David Cronenberg: Transformation opened to the public Thursday at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, and while it’s the first of a series of exhibitions to celebrate the director’s career, it’s also the one that reaches the furthest outside the film world itself to gauge the breadth of the director’s influence.

For Transformation, TIFF and MOCCA collaborated to commission six new works by contemporary artists looking to respond to Cronenberg’s catalogue. Together, the half-dozen MOCCA pieces make up three-quarters of TIFF’s entire Future Projections program, which may at first glance seem a rather oblique tribute to the director’s work, but it’s actually very calculated and precise.

Cronenberg, as a director, has always plied larger tropes of psychological and philosophical thinking, no matter what kind of goo was being spattered around onscreen, and cooking up a series of artistic responses allows those deeper themes to emerge from the blood-and-ectoplasm bath in chillingly distilled form.

The days of asexual dwarfs and exploding heads may long be in the director’s past — there hasn’t been a blatantly biomorphic splatter-fest since 1999’s Existenz, and even before that they were coming fewer and further between with M. Butterfly (1993) and Crash (1996) coming immediately before — but at Transformation, the old stuff still seems to be the most fertile ground for this group of artists, at least, in which to root work.

The derivations are both blatant and oblique. Seattle-based James Coupe offers one of the more engrossing, if not terribly engaging, projects with Swarm, a 360-degree set of surveillance cameras connected to a panorama of screens overhead. As you walk around the room, you’re captured, stored in a database and categorized for future use by age, race, gender and whatever other visual characteristics the program’s artificial intelligence can parse.

Then your image is placed on one of the panoramas with others of your kind: middle-aged white guys on one bank of screens, teenage girls on another. Coupe is making a nod to the weird self-exclusions of social media and how our increasingly fleshed-out online identities in fact narrow down and pigeonhole us into neatly definable categories — the better to sell to; just ask Google. The Cronenberg reference is loose, but imminent: think of the director’s fascinations with media and control. Videodrome, his 1983 feature, is about Toronto-based CIVIC-TV and its megalomaniacal owner looking to make a mint on pirated snuff films.

He stumbles into a covert government operation to eradicate low-life couch potatoes by means of a show, Videodrome, that implants malignant tumours in their brains and transforms their bodies, in Max’s case, into fleshy VCRs. A little extreme, maybe, but the melding of humanity and technology was a prescient glimpse into our hard-wired virtual lives of today, which Coupe reveals with calculated aplomb. The same connection could be made to Jeremy Shaw’s isolation-chamber piece, Introduction to The Memory Personality, where you enter a sealed room and endure a visual and sonic assault, all by yourself, aimed at “brain infiltration.”

All is not so oblique, far from it. Marcel Dzama’s Une danse des bouffons, a film piece, even with its Dadaist inflections and elements of turn-of-the-century avant-garde Paris (liberal references to expressionist cinema, Marcel Dumchamp, creepily fantastic costumes and creatures, the odd Harlequin here and there) pays its tribute in the most literal of ways: with the very visceral, nothing-held-back, bodily-fluid laden birthing of a full-grown man, close up and in detail.

The Cronenbergian nod comes into full focus with what follows, as a hooded woman gently licks the afterbirth from his face. Cronenberg completists will note the reference: in 1979’s The Brood, murderous, genderless trolls were spawned in pods, the product of their mother’s rage. The most controversial scene, of the actress tenderly licking a just-hatched dwarfling’s face, was excised from North American and U.K. versions of the film, to Cronenberg’s disgust (a later DVD release featured the scene as the director intended).

Whether Dzama’s work stands up as a work of art unto itself is another question, but rather than answer it, I’d rather move on to one that does. It’s Candice Breitz’s Treatment, and its simple elegance relies not on the visceral nastiness of the director’s oeuvre but the psychoses that underpin it.

Given the source material, this is no easy task. Breitz selects three scenes, again from The Brood, in which a psychologist, Hal Raglan, uses a radical therapy to help patients let go of past traumas.

In the case of Samantha Eggars, those traumas spawn the aforementioned asexual killer dwarfs (Raglan’s unique treatment creates disembodied pods, where they gestate, of course). But there is none of that here. Instead, Breitz selects three conversations between the therapist, Samantha, and another patient, Mike, carefully dissecting Raglan’s manipulations and controls as an authority — and, occasionally, surrogate parent — figure.

Breitz transforms the scenes by showing two videos, each facing the other: one, with the original scenes of the movie; another of a recording booth in which she, her mother, father and her own therapist provide voice-over that is then seamlessly dubbed onto the characters in the film.

The displacing effect is in itself a good hook; it sticks you in place long enough to listen. But the formal conceit is really a conduit into a potent personalization and assumption on the part of the artist of one of the director’s most personal films (no killer dwarves, The Brood was in part a parsing of Cronenberg’s failed marriage and subsequent custody battle for his daughter).

Breitz’s ownership of these traumatic moments strips The Brood bare of its blood-and-guts window dressing and exposes it for the intensely mundane, sadly universal terror it is: one of family drama, of love gone wrong. More than anything else here, Breitz gets to the heart of the matter: for all the wildly fantastical splatter and gore, Cronenberg’s concerns are fundamentally human. Who knew?